Zeljko Kojadinovic, MD- Neurosurgeon and Pain Specialist

CNS (central nervous system) infections are inflammatory processes of the brain and meninges caused by microorganisms. Due to the anatomical connection with the CNS, infections of the skull bones are also included.

In neurosurgery, infections caused by bacteria are most common. These are streptococcus, staphylococcus aureus and epidermidis, pneumococcus, enterococcus, listeria, etc. Today, specific infections such as tuberculosis and lues are rare. The portal of entry for a CNS infection can be an injury to the skin, bones, dura (one of the meninges), etc. Bacteria in the CNS can come indirectly through the blood from a distant part of the body (e.g., pneumonia), or directly as a continuation of the existing surrounding infection (sinusitis, otitis, bone suppurative osteomyelitis, pericranial infections, etc.).

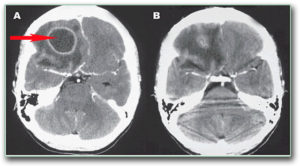

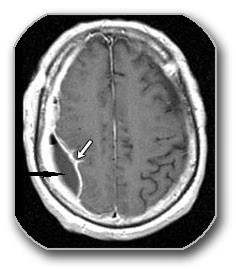

The infected tissue is initially red and swollen, followed by central necrosis and pus formation. Pus consists of dead tissue and special white blood cells – granulocytes. Depending on where the pus is formed, there can be abscesses (pus in the inflamed tissue) and empyemas (pus in an anatomic space, like pus in the space below the dura mater – subdural empyema).

The most common infections are:

- Osteomyelitis – infection of the skull bones

- Epidural empyema – a purulent collection above the dura mater (between dura and bone)

- Subdural empyema – pus collection under the dura mater (between the brain and dura)

- Brain abscess – a pus (purulent) collection inside the brain

- Meningitis, meningoencephalitis – inflammation of the meninges

These infections are often combined, and when isolated they give a similar clinical picture and their diagnosis and treatment are the same. On the other hand, the doctor initially suspects that it is a CNS infection, and only later differentiates which type it is. Therefore, we will present their clinical picture, diagnosis and treatment together.

The clinical picture of CNS infection is a combination of local effects of infection on brain and local tissues (e.g., epilepsy, neurological deficits, neck stiffness, headache, etc.) and systemic response to infection (fever, malaise).

The following questions must be addressed in the diagnosis:

-

- Which organ or tissue is affected by the infection?

- Is there a pus collection and where is it located? – The answer to these two questions is provided through neuroradiological methods with or without examination of the cerebrospinal fluid. The infection is suspected due to laboratory factors of infection – increased sedimentation, fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, neutrophil left-shift, high procalcitonin.

- Are there factors that lead to infection: otitis, sinusitis, a dirty wound, a foreign body, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid after a previous injury, immune deficiency? These questions are why the following are important: examination by an ear-nose-throat specialist (ENT), examination of injuries, and laboratory analysis of blood and urine.

- In addition to the infection, is there also meningitis, which often dominates the clinical picture and allows the cause to be detected in the cerebrospinal fluid?

- Can the microorganism be detected? – A specimen is obtained by microbiological sampling: swab from the primary infection (if there is an infected sinus, wound infection, middle ear infection); cerebrospinal fluid via lumbar puncture (in case of meningitis); blood (in case of bacteremia or sepsis) and/or pus puncture (if there is a pus collection).

- Is there CNS damage and to what extent (disturbance of state of consciousness, neurological and psychological deficits)?

- Is it an epidemic? – In case of an epidemic, especially with infections acquired in the hospital, it is important to determine all the links of the so-called chain of infection (sometimes known as Vogralik’s chain) – reservoir, portal of exit, transmission paths, the portal of entry and the type of microorganism.

Treatment always starts with conservative (non-operative) methods. Antibiotics come first. Other therapies can include antiedema therapy, analgesics, antipyretics, and hydration. In case the CNS is affected, antibiotics are chosen that can cross the inflamed blood-brain barrier (a blood-nerve barrier that can be penetrated only by some drugs). The decision is made according to the antibiogram, but often, due to the urgency of introducing therapy, it starts immediately and empirically after taking the sample. Combinations of newer broad-spectrum antibiotics are always chosen and administered parenterally (especially if given empirically).

Surgery is performed in case of more severe forms of pus collection in the skull. Primary infections of the face and ears are surgically treated by an ENT or maxillofacial surgeon. Infection of the skull is surgically treated by a neurosurgeon. If the pus collection inside the skull does not recede in response to conservative therapy, surgical pus evacuation is indicated. The reason for this stance is that in most patients, a sufficient concentration of antibiotics is not achieved in the pus. Today, the tendency to evacuate pus by minimal surgical methods dominates (using a smaller opening in the skull, and removal of pus with a syringe, rinsing and possibly placing a drain in the cavity for another 2-3 days). We may also decide on larger operations that involve the removal of the walls of the pus collection. Indications for this are if there is a collection with walls that is resistant to treatment, or a foreign body, or some microorganisms.